The Cotonou LAB presents, from April 30, an exhibition of Bruce Clarke, whose works are from the Zinsou collection.

From the anti-apartheid struggle to the work with civil society and Rwandan institutions on the genocide memorial, Bruce Clarke combines commitment and aesthetics.

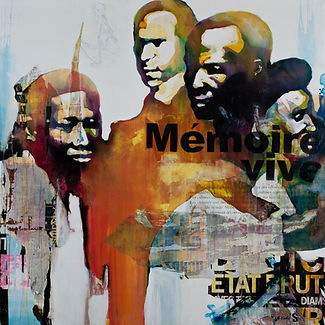

“Plastically, I start from torn fragments, various papers, newspapers, posters, and I work them, triturate them, impregnate them with colors. Words and colors, words and images are then integrated and recomposed on the canvas. The texts do not necessarily have an immediate link with the images, some do not illustrate the others, I do not comment, I recompose from a 'flattening' of the figure. The documents come from a certain context which also clarifies the place of the media, the press, television images and everything that assails us daily and they are then transformed and replaced in another context which is above all a mounted canvas. on frame.

My works evoke a certain number of situations from more or less contemporary history. It is not with a work of art that we change the world. The main thing for me is to recognize the forces against which we must fight. »

The South African artist offers us his work as a springboard for reflection, thus putting art at the service of thought, by pushing the viewer to question himself freely on fundamental principles. Art, for Bruce Clarke, is a privileged way to express oneself, to inform and to take a look at the world around us by arousing a questioning, a thought. Like a freeze frame, the work is there to ask a question, his work suggests more than it reveals, leaving no room for indifference. More than ever, the viewer is active and free in front of the work, thus reclaiming their own story.

Click on the icon to download the book With Bruce Clarke from the Zinsou Foundation editions

Identity and identities

Emilie Zinsou

"Let's define Bruce Clarke.

Well, let's. It's all very simple.

Bruce Clarke is an artist.

Let´s start with a simple premise: The artist´s medium is canvas. Therefore he is a painter. His paintings - the largest of which cover an entire wall and strike the viewer at first sight and the smaller ones, which require long contemplation, up close and at a distance, in order to reveal their full significance - speak to us in a language that we presume to master. Saying that Bruce Clarke is a painter is no lie, as evidenced by the wall labels (polymer paint and collage on canvas, watercolour and collage...); saying that he paints figurative pieces featuring fragments of text that provide leads for the viewer as to their subject matter is merely a way to present the work in its most obvious and immediate aspects.

And in fact is that all there is to say?

Bruce Clarke does paint, but that is hardly all he does: he creates film posters, installations, he works with writers, poets, journalists, and even his "classic" paintings are much more than pictorial figurations. Standing in front of « l’Humanité » or « Life is war » the viewer scans the canvas, pondering the questions they raise. Then he gradually uncovers the various "layers". Layers of texture and materials - paint of course, but also papers, pictures, newspapers... - and layers of meaning. Do these paintings tell us of a man, a woman, of physical pain or of the state of the world? The artist becomes an author, an inquirer. The codes of painting we think we master are left behind and the painting reveals its essence as critical figuration: reflecting on the artist´s technique is a first step towards reflection on the use it is put to. Sketching, painting, collage, creation... the full development phase results in much more than a painting, both in its material completion and in the thought process that it involves. The work of Bruce Clarke, although it proceeds from a common and constantly evolving approach, is so diverse that it would require calling its creator a "mixed-media artist". Yet again, the words hardly seem to do justice to the full scope of the artist´s work. If, in the words of the artist himself, creation is embarked upon first and foremost for beauty´s sake - to bring to light a certain artistic vision, an aesthetic insight - it is also a vector for meaning. And the significance of his pieces grows clearer and more defined from one stage of creation to the next, from one project to the next. He depicts the world as he sees it and expresses his refusal to accept a preconceived version of it: as he points out predetermined ideas and ready made "truths", he encourages us to consider their exact implications and he helps us to identify them. His paintings are both new ideas and old continents, stories of struggles and living memories, questions and rebellions. In this respect Bruce Clarke is indeed an artist; but this definition, however essential, is far from sufficient.

Bruce Clarke is South-African

Where do you come from if you make your home all over the world?

Does being born in London make you English?

Are you South African because your parents are?

Does the fact that your maternal family defines itself through the previous generation´s religion and origins make you more of a Lithuanian Jew? Should you be Mexican if your brother is?

Does living in France make you French?

Bruce Clarke is all of those things and none of them at once. Just like the men he portrays in his work, his positive identification eludes those who try to define it. Born in 1959 in England, he studied Fine Arts at Leeds University and lived in Great Britain until his departure for Mexico, where he spent almost five years before settling in France. Although established there, he frequently travels; always on the move, on the look-out, from one creation to the next. A British citizen in that case?

Yet he spent most of his youth surrounded by exiled South Africans fighting against apartheid. His world already spreading beyond seas and continents. Should that be South African then?

Notwithstanding the fact that he is one of the artists most identified with South Africa, it remains primarily a reasoned notion, a connection, a struggle. Coming back to South Africa is not a "homecoming", telling the world about its suffering and its realities is a way to analyse, to fight, to depict a reality of apartheid that beggared belief. The artists!– who was permitted to visit South Africa for the first time only at age 31!– doesn´t seek to make this land his own more any than any other.

Thus!– like this "rainbow nation", which, like so many others on the continent, encompasses so many identities, languages colours and communities! – Bruce Clarke does not lay claim to a particular territorial belonging or nationality. All things can and should be explored, and neither the identity of the artists, nor that of the viewer should stop them from considering the world freely. So let us forget where we ourselves come from and reflect on what the artist tells us.

Bruce Clarke’s work is politically committed.

Faced with a Bruce Clarke painting, the viewer may choose what he sees. At first sight, it is beautiful, forceful, impressive; it looks like no other work of art. The viewer can look upon the painting with a mind free from questions and bask in the pleasure of observation.

But the works also “speak”… They include words (headlines, article excerpts…) and even convey a message that goes beyond what is written. The writings within are not a caption for the images, a prearranged account to guide the onlooker. The titles of the pieces steer us in a certain direction: they some-times resonate in their stark inevitability!– Le pauvre exploite le riche, Alone, Precarious lives!– and some-times require more consideration, more scrutiny!– Trouble Ahead, En face des barbares.

They can convey suffering, they can speak of freedom, they can describe a genocide or recount a boxing match.

Yet the artist merely seeks to suggest, to create a spark that will set us thinking. In essence he chooses not to act as a guide; he gives us leads but does not compel us to follow them. His art is not political. His work´s commitment is not a program, an ideology or a shrink-wrapped set of notions to help the viewer sleep at night. It does not seek to provide "satiation". And if does provide an explanation, it is merely that we are free to think and understand by ourselves.

Creating art does not change the world accord-ing to the artist. However it is in fact when we are faced with his work that we are given the best opportunity to dissect the world, to think about it at lei-sure. And, if we ask questions and search for our own explanations about the subjects they broach, maybe they end up doing more for us than if The great questions that resonate throughout his work are also the questions that have permeated contemporary history.

Bruce Clarke explores identity and identities.

From one painting to the next, Bruce Clarke explores subjects that define men, their roots, the way the world defines them and the way these definitions divide them.

The artist asks a question: what does it mean to be Black? For him, who is white for some, black for others, and who has had as many nationalities attributed to him as aspects to his work, being black is more a question of history than it is of colour. To be black is to be the boxer who rises against the tide of American racism at the turn of the century, it is to be the ANC freedom fighter whose skin colour has ceased to matter, it is to feel the suffering of the Rwandan people, torn apart on the strength of hollow external criteria. But, above and beyond a question of colour, it is the humanity within each of us, our perception of the Other, that we are brought to admit or to question.

This theme, revealed through the paintings, begets a question itself: what does it mean to be a people? The modern world gives us a restrictive definition concerned with borders, languages and com-mon customs, criteria established by a historical or modern-day domineering "Other", whatever the reason. And yet the visions, the heartache, the men that are depicted, are all linked by something greater than a mere territorial belonging. They find an echo in us that comes from far deeper than the criteria that seem to define us.

And so it is that all the questions and commitments of the artists can probably be boiled down to a single fundamental question: what does it mean to be free? Bruce Clarke show us his vision of free-dom, not as a belligerent allegory, but as a concept that we are free to make our own, by resisting illusions and identifying the forces that we must take arms against. The message contained in his work is not to be found on the canvas but in what the canvas awakes within us. It is first and foremost a matter of questioning accepted "knowledge" and authorities: whether it be news reports that construct a certain message, rulings from those who lay claim to certain categories of knowledge!– policemen, professors, politicians or even artists… Creation is not there to replace knowledge but to encourage each one of us to increase it. If it is justified to mention the artist´s commitment then this commitment is on a par with that of the people who refused apartheid, who questioned the widely accepted version of events given by international press agencies in Rwanda, who do not consider the North-South relationship to be one of justified domination, who overcome epistemological obstacles and do not balk at complexities and paradoxes, people who seek the truth whether or not it is a comfortable one; it is a commitment that urges us not to accept that a particular source may act as a supreme authority leaving us unable to seek answers for ourselves. That is the commitment that runs through his work.

Therefore!– and according to the artist himself!– when we look upon Bruce Clarke´s work, the identity of their author is of little consequence. And if it is known!– or believed to be known!– it is by no means a reason to blindly accept what we think it reveals.

And, in the end, the true mark of our identity, of our humanity, is to think, to explore and to be free. Free even of any definition.

So is it really necessary to define Bruce Clarke ?

Text published in ABC, With Bruce Clarke, 2012, Fondation Zinsou